The High Court has declared as unconstitutional critical sections of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act (SPVA), effectively overturning prohibitions on the saving, sharing and sale of uncertified seeds by smallholder farmers.

Hearing a petition filed in 2022 by a group of 15 smallholder farmers, the court, presided over by Justice Rhoda Rutto, found that several provisions of the SPVA violated constitutional protections and unduly discriminated against small-scale farmers.

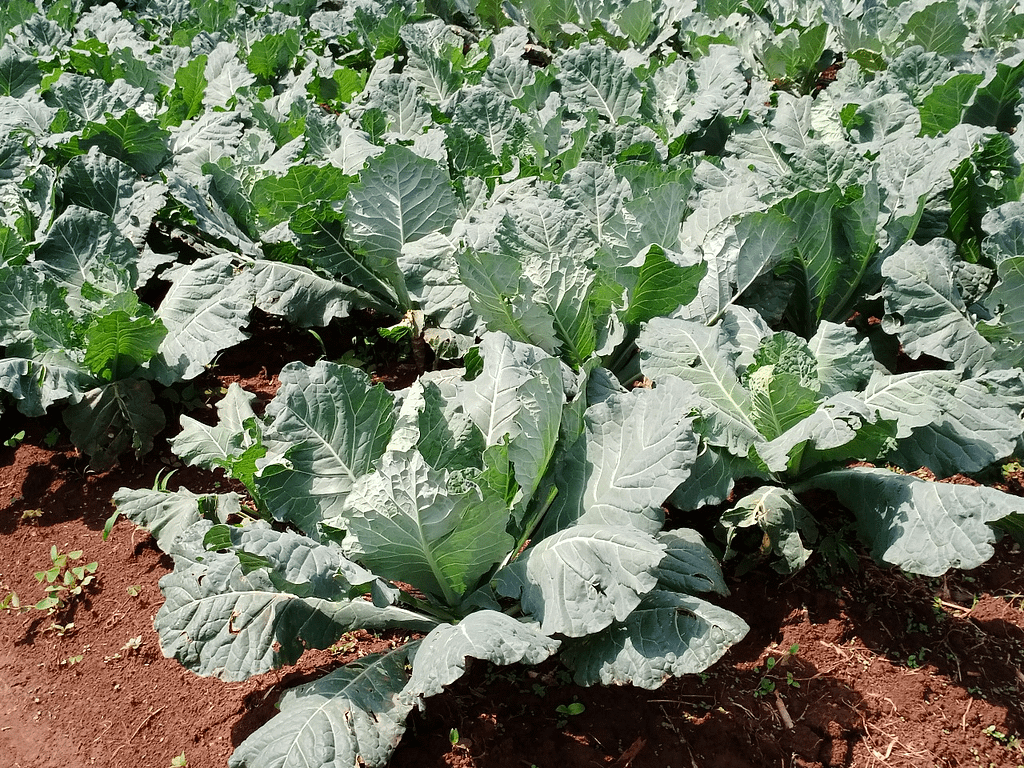

Among the offending provisions that were struck down is the clause criminalising the processing, sale or exchange of seeds that were not formally registered under the law, including traditional and indigenous varieties commonly used by rural communities. Under the Act, offenders faced up to two years’ imprisonment or a fine of KES 1 million.

The provisions granting state inspectors sweeping powers to raid community seed banks, seize seeds and penalise farmers involved in informal seed exchange were also struck out.

The sections that reserved seed trading and distribution rights exclusively for registered seed merchants or certified seed producers, denying farmers the right to use, exchange or sell their own harvests, were also found to be contrary to the Constitution.

In her ruling, Justice Rutto determined that these restrictions infringed upon farmers’ constitutional rights, including their rights to culture, livelihood, property and equality, and upheld the legitimacy of what is widely known as Farmer-Managed Seed Systems (FMSS).

The litigation was spearheaded by smallholder farmers from across Kenya, represented by legal counsel, including advocates from the Law Society of Kenya (LSK), supported by civil society organisations.

They argued that the SPVA effectively criminalised ancestral practices of saving, sharing and exchanging seeds—practices that have sustained rural communities for generations and underpin Kenya’s agro-biodiversity and local food security.

Further, they contended that the law privileged commercial seed companies and breeders, granting them broad proprietary rights, while denying any corresponding rights to farmers who maintain and conserve indigenous seed varieties. This, they argued, amounted to unequal treatment and a violation of constitutional guarantees.

The verdict effectively decriminalises informal seed exchange and returns seed autonomy to millions of smallholder farmers across Kenya.

This means that community- and household-level seed banks, which for decades have preserved local, indigenous and climate-resilient varieties, are now legally protected from state raids or seizure.

By recognising FMSS as legitimate and constitutional, the Court has rebalanced the legal framework in favour of farmers’ rights, culture and food sovereignty rather than corporate or commercial seed interests.Lead petitioner Samuel Wathome said the decision was a vindication of tradition: “My grandmother saved seeds, and today the court has said I can do the same for my grandchildren without fear of police or prison.

”From civil society, Greenpeace Africa hailed the verdict as a victory for food sovereignty and environmental justice, noting that indigenous seed varieties are often better adapted to local soils and climate—vital for resilience against drought and climate change.

Agro-ecologists and biodiversity advocates emphasized that the ruling safeguards Kenya’s genetic heritage and preserves the diversity of crops essential for ecological balance, dietary diversity and sustainable agriculture.

Farmers across the country may now resume traditional seed-sharing, saving and selling without fear of prosecution.